Oculus has come a long way since its booth full of chairs and televisions at E3 2014. The Facebook-owned VR company has fully embraced standing and movement in VR, an evolution from Rift’s “seated-only” beginnings.

Five years after a terrifying Alien: Isolation demo (that never materialized into a full VR experience), Superhot’s outstanding first showing, and Lucky’s Tale’s humble beginnings, the Oculus booth is a tribute to full-body, full-motion VR. Large plexiglass enclosures exposed to the show floor put players on stage for anyone walking by to observe.

The chairs are gone, as are the large televisions. Now, a small PC monitor operated by a demo guide is used to load up any number of previews on hardware. Players are given room to move around the space and interact with the immersive virtual worlds.

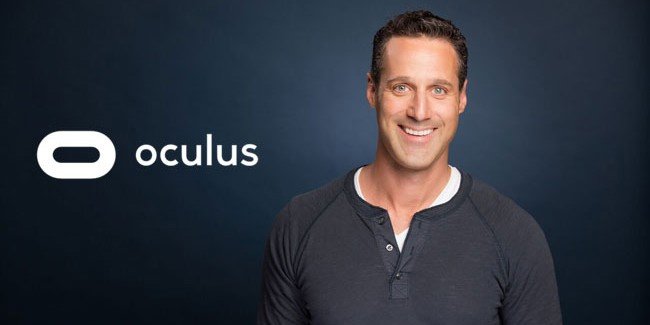

“We need more space now,” said Jason Rubin, Facebook vice president of special gaming strategies told GameDaily at E3 2019. “With these inside out tracked headsets, even with the corded Rift S, more space is necessary, because you can move more. Back in those days, we didn’t have three external trackers, we had two. So, you had to face forward, and you could only go a couple meters by a couple meters.”

This year, Oculus was still showing off seated experiences –like Phantom, a game in which you row and shoot from a “tactical kayak.” It’s a strange pitch, especially if you see someone flailing wildly without understanding what they’re playing.

“It was one of the weirdest pitches I’ve gotten,” Rubin said. “And it turns out it’s awesome, because.. your brain just goes, yeah, I’m there. This is one of those where even if you’re not a kayaker, because I’m not a big kayaker, it just works. You just forget the fact that you’re not on the water. The locomotion just works. And again, you’re seated.”

I had the chance to preview two games designed for the Oculus Rift S, the company’s modest update to the original Oculus Rift. Unlike the original consumer headset released in March 2016, the Rift S does not require external tracking sensors. This means that players can move and turn. They are limited by the Rift S’ cable, as the new version is still tethered to a PC.

“It’s evolutionary. It’s not revolutionary,” Rubin explained. “Think about consoles. You can update the console, smaller form factor, lower costs, all of that. If it plays the same software, same ecosystem. It’s a different device, but it’s the same ecosystem. PlayStation 5 may play software that you can’t play on 4. That’s a new ecosystem. This is the same ecosystem.”

My first demo on the Rift S was an upcoming game from Sanzaru, Asgard’s Wrath. I immediately started getting God of War-meets-Skyrim vibes, as I walked into a tavern to meet the local color, including the trickster god Loki.

The demo picked up after the fledgeling god protagonist slays a kraken in battle. Loki has taken an interest in the new deity, offering to counsel him on the ways of godhood. While we’re certain this will go bad in the long-run, the charming and mischievous god was on our side (for now). He tasked me with helping a shieldmaiden seek revenge on Tyr, who killed her brother.

Asgard’s Wrath isn’t quite open world, instead offering large hubs to explore. Each has their own human protagonist, puzzles to solve, and monsters to fight. The first step in aiding the shieldmaiden was figuring out how to inhabit her body and interact with the physical world. Once I had it solved, Asgard’s Wrath took on elements of SNES classic Actraiser.

The fledgeling god can move between towering god mode—which allows the player to use powers like mutating animals into warrior companions—and human avatar mode, which is where I was able to explore the island. The blend of puzzles and action felt balanced for the 20 minutes or so I played, and using a direct movement option (rather than standard VR teleporting) presented only the most minor vestibular discomfort. This in itself is evidence of the growth of VR game development in the years since Oculus Rift first became available for pre-release demonstration.

The second game I played, After the Fall from Arizona Sunshine developer Vertigo, I stepped into the shoes of an ice age survivor. Set in California in 2005, After the Fall is a cooperative zombie shooter. Instead of the typical zombie outbreak, the game’s “Snowbreed” are born from drugs developed during the 1980s.

Players can team up with a friend to scavenge civilization’s remains. A developer jumped in with me to show that the game was co-operative, but largely stepped back in an attempt to make me feel like I was a “natural.” While it was a strange demo decision, the game itself felt like a great evolution of Arizona Sunshine’s formula.

After the Fall’s unique weapons, like an Iron Man-style, wrist-mounted rocket launcher were great fun to use. The one drawback was a platform limitation. After the Fall not only encourages, but requires 360 awareness. The Rift S is still a tethered head-mounted display, and I felt like the person handling my demo was constantly rearranging my cables like a bridal train as if he were my Maid of Honor in a zombie-themed wedding.

Time in room-scale VR with the Oculus Rift S drives home the power of Quest’s untethered technology. After the Fall is the kind of game I want to play without having to worry about whether I’ll be tripping over cords.

According to Rubin, Quest is catching on because of low barriers to entry and reasonable pricing. Accessibility has driven the Quest to achieve more than $5 million in software sales in the system’s first two weeks. Before Quest, walking into an electronics retailer looking for a virtual reality HMD was probably a disappointment, especially if you didn’t already have a capable PC. Your options before Quest for sub-$1,000 startup costs were PlayStation VR or Oculus Go.

Despite the rapid adoption of Quest, Oculus still sees a two-product future. Quest isn’t a replacement for tethered VR. The software investment strategy mirrors that.

“From Oculus’s standpoint, we’re going to push [developers] to make something that works on Quest and then looks as good as it can be on PC,” Rubin explained. “At the end of the day, the glory of VR is a lot in the being in a different world and doing different things, and for most people, it’s not the graphic fidelity, right? So, something like Beat Saber could easily have come first on Quest. It wouldn’t have looked any different than it does today. Vader Immortal is another great example. Came out first on Quest, because they focused on that for the launch. It’s coming out on Rift. It’s going to look so much more beautiful on Rift, because the PC is more powerful. It’s the same experience, and you’ll love it on either one when you play it. Phantom, I’m sure at some point will come out on PC, but it was built for Quest.”

Rubin says that developers are free to focus solely on Quest or Rift S. It’s just that Oculus may not fund those projects right now.

“I will not categorically say no to anything,” Rubin stated. “Some developer might come in and go, ‘Listen, we think the future of VR is this type of title. It won’t work on Quest.’ Let’s just pretend for a second it’s entirely physics-based, and physics is a CPU-intensive process, and at least today, Quest can’t do it. And we think about it, and we go, ‘That’s genius. We’ll fund that for PC,’ because if it works on PC, someday it’s going to work on Quest, and that pushes VR forward. So, that’s the title I would do for PC.”

The same is true of Quest-focused titles. If a developer can evidence why it focusing exclusively on the Quest is the right decision for that project (and not just because of preference), Rubin will give it consideration for funding.

Oculus has always heavily curated its software offerings. Adult content has typically been off-limits, for instance. During E3, Oculus made waves by shutting down the ability for Virtual Desktop users to stream content from Steam VR to the Quest. It has been largely seen as an anti-consumer move to protect Oculus’ own catalog. Rubin offered a different explanation, though declined to speak specifically about Virtual Desktop.

“We’ve made a decision on all of our platforms to curate to a certain extent, and keep a certain quality bar,” he told us. “If we didn’t do that, even on the Rift—which the curation is pretty light on—you’d have things that just don’t work at all, or they run at a few frames a second, because the developer was like, ‘I’m done. I can’t optimize this. I’m putting it out.’ And it’s uncomfortable. And it doesn’t work. There are other things that would work on some people’s PCs, but not other people’s PCs, because they didn’t want to QA it, or whatever. And so, we had to set a bar. On Quest, we’ve set a higher bar of curation than we set on Rift, and it’s not because we’re elitist and we don’t like indies. That all is nonsense. Beat Saber is the indie-est of all indie titles. We’ve spent a lot of money on indies. In fact, 90% of what we ship is indie.”

While Rift is often thought of as a PC peripheral, Quest’s standalone nature has created a different mindset and usage pattern. It doesn’t demand the level of tinkering that PC users are often used to and tolerant of.

“It’s about having a consumer pick this up—like they do a PlayStation, Xbox, or Nintendo—knowing it’s going to work, it’s going to be a reasonable quality, and it’s a reasonable price point,” Rubin explained. “And so, everything we do, from the day that we take a submission, to every update, needs to maintain that quality bar. If something’s not working for a lot of users, not cool. If something is making users uncomfortable, not cool. If somebody, and this has happened, submits a video app, and the videos are all pretty cool, and then they put it in the store, and they update it with things that are against our policies, we’ll make a stink about it. If somebody submits something in the store, and the app is fine, and the icon is fine, and then they change the icon to have some… whatever… to attract your eyeballs, yeah, we’ll make a stink about it.

“It’s the right thing to do for consumers. It’s also—and this is the hardest thing for people to understand—the right thing to do for developers, because what we’re seeing with this device is console-like usage. That’s hours of usage that you would have on a console. And we’re also seeing buying habits that you would see on a console. And I believe that that is largely because everything’s good. And so, every time something boils up, ask yourself, was this a high quality thing, or was it in other ways detrimental to the ecosystem, harming the consumer, or harming the developer ecosystem? Not an easy business to be in, but that’s the answer.”

GameDaily.biz © 2026 | All Rights Reserved.

GameDaily.biz © 2026 | All Rights Reserved.